In my summer holidays - I must have been about six or seven - I used to spend all day cycling around my grandparents’ house in the outskirts of Como. It was a small neighbourhood where everybody knew each other and I would often stop by Mr. Loris, a mechanic who lived nearby, in order to pay him a visit. He was always working in his garage, a perfectly clean and tidy place where he used to restore and collect a few vintage Moto Guzzi motorbikes. They were painted flame red, shiny with polished chrome, and sometimes Mr. Loris would turn on an engine for me or let me climb on the saddle. I dreamt of having, one day, a workshop just like his. And as I rode back home for dinner, I’d envision myself speeding on a red and shiny Moto Guzzi, instead of my purple and pink girls bike that I got from my cousin when she grew up.

At home, I would park my imaginary Moto Guzzi in the shed, next to a dusty road bike on which my dad used to compete locally in his younger years. Although his racing days were over, he (luckily!) refused to get rid of it and kept it as a keepsake. I have never seen him riding it, but sometimes he dusted it off a little bit and checked that every mechanism was still functioning. And although he knew it was way too big for me, one day he decided to let me try it: he removed the toe straps, lowered the saddle, inflated the tires, then proudly watched me push on the pedals and gain speed down the street. It was then when we both realized that I couldn’t reach the brakes.

So it ended my very first ride on a vintage road bike: with some disinfectant and band-aids for me, a big scare for my dad and some more years of oblivion in a dark corner for the bike.

Years went by and I became a student at the University of Milan. Watching my classmates riding around in the city’s warm spring days made me want to have a bike to join them, also to commute from the train station to the Atheneum. Problem was, every decent bike parked outside the station overnight was a tempting target for thieves: I needed an old bike that would pass unnoticed, with almost no value and just the basic parts for me to ride it. Exactly the kind of bike that years earlier gave me a permanent scar on my left knee, as I desperately tried to stop it from running downhill without being able to brake.

Thanks to a childhood spent playing with Lego, I always had a knack for assembling and disassembling stuff: repairing a bike was a slightly more difficult challenge that I was willing to undergo. I was curious and ready to learn. So I brought the old bike back to light, took possession of my grandma's garage where I would find a workbench, a bunch of old tools, rags and gloves, and I started stripping down the bike. As the works went ahead, I gradually became aware of the overall quality of the bike: under a thin layer of dirt, the alloy parts branded "Campagnolo" still shined and worked perfectly well. Their design was elegant yet practical. And the dusty frame turned out to be painted in its original color, a beautiful hue of sparkling dark blue, with yellow engravings and decals which read the brand “De Rosa" on the downtube. Every single piece of the bike came off and got back up so smoothly that I felt I had something special in my hands, something that stood the test of time and possibly came to me with even more charm. That was definitely not a bike that was meant to be abandoned outside a train station. It deserved to be brought back to its original status of a purebred racing bike.

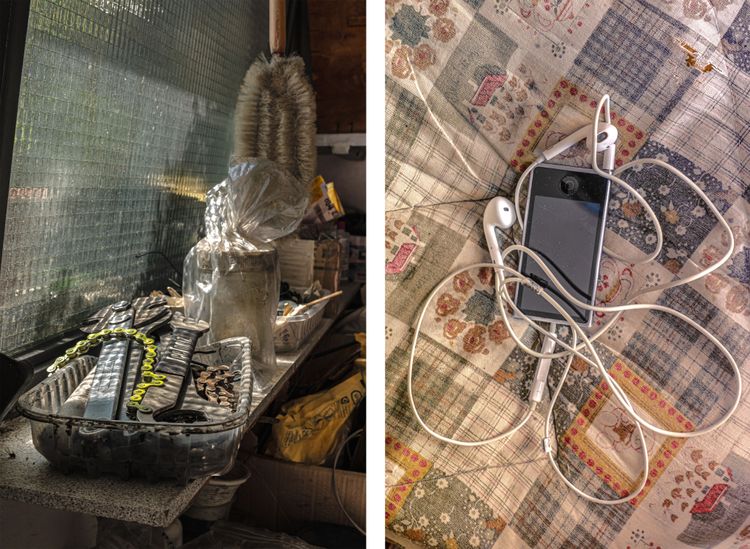

That was my first restoration project. I carried it out slowly and carefully, fearing that I might unconsciously damage something and at the same time figuring out how to solve each and every small problem that forty- year-old components might pose. I learned that toothbrushes and pipe cleaners are essential tools for cleaning thoroughly, or that small marks and scratches on the paint add value to a frame, because they are the patina of history; I learned how to measure the diameter of loose ball bearings which inevitably fell on the floor and got lost. Most of all, I realized that aproper restoration job means a lot of patience: for me, every single part of a vintage bike needs to be disassembled, cleaned and checked from bolt to nut. Eventually, the missing parts need to be found, and I won’t be content with replicas: waiting for the original and period-correct replacement to pop up may be time consuming, but it adds value not only to the finished bike, but to the entire process of bringing it back, as close as possible to the concept of the master craftsman who designed and built it.

Finishing the De Rosa took me several months, but as soon as I completed its restoration, I felt that I could start all over again: there were so many bikes that deserved to be saved from decay, each one with its distinguishing building features that made it almost unique. At the same time, details like the shape of the fork crown or the filing of the lugs could act as a signature of a specific framebuilder in a specific period; there was still so much to learn. And so, more and more frames piled up in my grandma’s garage as I began to colonize it entirely for storing all the spares and the works in progress. I found some good friends with whom I shared my passion: Alex, Andrea, Daniele, Jacopo and Luca. We would go together to any flea market and look for rusty parts, or we would help each other with repairs, or to spot some interesting frames around town and ask for information. Thanks to them, restoring a bike was no longer a matter of mere mechanics: every job felt like a celebration that would leave us grateful and happy, although miserably dirty.

Four years ago, Daniele, Alex and I opened an Instagram account called Cyclico, where we post pictures of our bikes and of the events in which we participate. We also help new enthusiasts to choose and build their own bikes, and share with them some historical facts. Our approach to vintage cycling couldn’t be more different: Daniele is a racer, always ready to jump in the saddle and hurl his bike down a high-speed track. Alex is the cycling nomad of the group: he pedals around beautiful places such as Sardinia, discovering new routes and often ending his rides on a sunny beach. As for me… If you’re reading this article, you should have understood by now what I like to do. Yet, we really enjoy hanging out together and discussing new ideas, along with a variety of projects for the future. Cyclico is the perfect sum of our essence and our diversity.

In July 2022 our first vintage ride took place: It was a small and relaxed event, with a familiar feeling and tons of fun, as we rode a few kilometers and then shared a couple of beers with lots of old and new friends. Well, I didn’t really pedal: that was Daniele’s business. I was there as the peloton mechanic and, of course, for the beer. We called the event Fast Rust, and we are already planning next year’s edition.

In 2019 I did participate in L’Eroica in Tuscany, though: a beautiful experience that ended too soon, because the sole of my cycling shoes tore off halfway and I had to pedal barefoot for a few kilometers more. Nevermind: I have a modern MTB with which I ride on trails in the woods whenever I feel like it, without the fear of losing some little parts made in the ‘60s or ‘70s which are now almost impossible to replace. Vintage bikes are fun to ride, but for me the best is still playing Indiana Jones with my friends and discover some forgotten frames that sit untouched somewhere in a dark basement. I don’t do it because I think that a fifty-year-old bike can compete with modern ones: technology has improved greatly and radically changed for the better the experience of cycling. Guess it’s just a mix of curiosity, desire to learn and to test my knowledge facing practical issues, the unique appeal of chromed and colourful steel frames and the admiration for the superior craftsmanship skills of people who built them entirely by hand. All of this doesn’t make me a professional restorer, and that’s perfectly fine with me. I like to keep my passion the way it is: a way for me to discover, create, spend some great time with great people and have fun while playing with rust.