It starts as a wild idea: two weeks of cycling to clear my head. But what was meant to be a personal challenge grew into the Glorious Glacier Ride, a 1,600-kilometre journey through the Alps, past melting glaciers. Together with a small group, I cycled from Munich to Monaco with 35,000 metres of elevation gain in my legs and a much heavier burden on my mind: the visible consequences of climate change.

This year has been declared the International Year of Glacier Conservation by UNESCO. The official opening will take place in March at the UNESCO office in Paris. That seems to me to be the perfect moment to launch the Glorious Glacier Ride, after which there will be no turning back.

We set off on a crisp morning in Munich. The city is waking up and at 9 o'clock we are waved off by the deputy mayor and an ambassador of the European Climate Pact. There are four of us in the core group: Jos, Pepijn, Nathalie and me. Along the way, about twenty other cyclists join us for one or more days. Scientists from ETH Zurich and Université Grenoble Alpes tell us about the Big Melt. Their message is confronting : even if we stabilise global warming now, glaciers will continue to melt. Yet there is hope: if we adhere to the Paris Climate Agreement, half of the current volume will be preserved.

Cycling and cleaning up CO₂

The trip is physically demanding, but the effort goes beyond the endless climbs. Every participant automatically takes part in the first Carbon Crowd Sinking campaign. The rule is simple: everyone cleans up as many tonnes of CO₂ as their age. For me, that means 53 tonnes. Because removing one tonne of CO₂ through our campaign costs 150 euros, my target amount is almost 8,000 euros.

This approach makes it tangible. Your age is directly translated into responsibility: the older you are, the greater your share in historical emissions – and therefore the greater the contribution you must make. In exchange for a unique postcard, we encourage friends, family and colleagues to clean up part of their CO₂ emissions.

First stages: wet and snowy

28 August. We arrive in Ehrwald soaking wet. The mayor welcomes us cheerfully, but with a serious message: winter sports are less of a given, summer tourism is becoming the new driving force.

Two days later, the Stelvio awaits us. It is snowing at the top, as if the mountain wants to test us. During Stelvio Bike Day, thousands of cyclists struggle uphill. During the climb, I overtake a lot of riders and tell them why we are cycling to Monaco. ‘Climate change, yes,’ says a German, panting, ‘but right now I'm mainly thinking about those last few bends.’ I have to laugh: awareness sometimes requires the right moment.

Flying hours to Cape Town

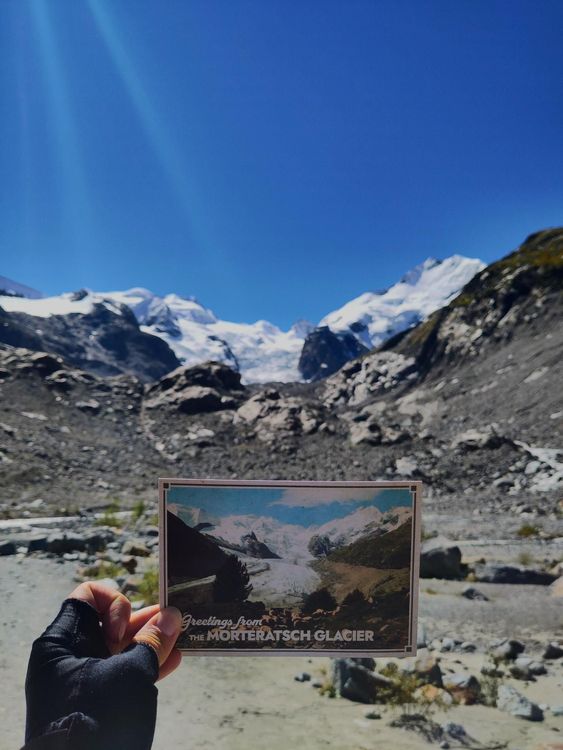

31 August. The sky is clear blue at the Morteratsch Glacier. The view is beautiful and painful. The glacier is a shadow of its former self. Right in front of it is a pole displaying the flying hours to tourist destinations such as Cape Town and Phuket, sponsored by an airline. Cynical: tourists fly thousands of kilometres to see a melting glacier, and it is precisely that flying that contributes to it. Pepijn turns the sign around so that the logo disappears. A small act, but a satisfying one.

What makes the trip special are the conversations. In Thusis, the mayor waves us off with all his staff, and in the evening he himself buys one tonne of CO₂ through our campaign. In Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, we have dinner with a local action group that opposes an unnecessary and expensive railway tunnel. A ski instructor tells us how she sees the snow disappearing further every year.

Every time we meet a mayor, we seize the opportunity to make a clear appeal: stop fossil fuel advertising in public spaces. Because as long as airlines, cruise companies, oil brands and car manufacturers are free to advertise their SUVs, they will continue to paint an inaccurate picture of what is normal. The glaciers we see disappearing along the way are proof that there is nothing normal about continuing on the old path.

Sometimes it's chance encounters. On the Passo del Bernina, a man in an Audi TT approaches me and immediately decides to contribute 150 euros. On the Col de l'Iseran, Pepijn and I talk to three Dutch motorcyclists. Later, we receive a message that they too have invested through our campaign. Moments like these give us courage.

Glaciers disappearing

The Furka Pass takes us past Hotel Belvédère, famous from James Bond's Goldfinger. The hotel stands empty, windows boarded up, its grandeur gone. The Rhone Glacier has receded. Just behind the souvenir shop was the Eisgrotte, supposedly “temporarily closed for maintenance”. The truth is more poignant: there is no ice left. All that remains is a pile of white cloths that were supposed to slow down the melting. Researchers explain that this is a false solution: good for marketing, but ineffective.

In Zermatt, we experience the opposite. The village is thriving thanks to winter sports, which are more popular than ever due to its high altitude. For now, climate change even seems to be beneficial. Yet it is a precarious balance. We take the Gornergratbahn to 3,000 metres. Above, our flag and banner fly, tourists listen attentively, but often shirk responsibility: the cause always lies elsewhere.

In Chamonix, the director of the Office du Tourisme and a journalist from Le Dauphiné Libéré welcome us enthusiastically. After a welcome beer, we get creative and, brainstorming, come up with an idea: why not introduce a nature contribution alongside the tourist tax? Then visitors would automatically invest in nature conservation and we would offset our emissions. To me, that makes sense, just as obvious as not throwing your rubbish on the street but in the bin.

Cyclists with stories

The strength of the tour also lies in our team. Jos, at 62 the oldest member, turns out to be a natural talent at making cheerful vlogs for our Instagram page. Pepijn not only cooks healthy meals, but also shares his knowledge about regeneration and CO₂ storage. Nathalie, a psychologist at MeteoSwiss and always reaching the col first, is visibly moved by the sight of the disappearing glaciers, even though climate change is her daily work. Together we form a group that supports each other, both literally on the bike and figuratively along the way.

After two weeks and 35,000 metres of climbing, we arrive in Monaco. The contrast is striking: from quiet mountain valleys to traffic jams filled with Porsches and Maseratis. We are welcomed by a delegation from the Prince's cabinet and filmed by Monaco TV. After the champagne, I take a dip in the Mediterranean Sea. This year, it is record warm: three degrees above normal. Climate change is not limited to the Alps.

For the glaciers and ourselves

What started as a personal adventure grew into the Glorious Glacier Ride, a journey full of encounters, experiences, teamwork and confrontations with reality. The desolate sight of the melted Rhône glacier on the Furka Pass is disheartening. Standing there, I felt the real impact of climate change. The reality is that much more is needed than a bike ride.

Along the way, I often thought: how can we make this bigger, how can we ensure that more people see the glaciers, feel this and take action? Awareness alone is not enough. But thanks to the Glorious Glacier Ride, we have at least reached a lot of people. This has enabled us to remove 160,000 kilograms of CO2 through the Carbon Crowd Sinking campaign. That makes a difference: and even though it's not enough, it's at least something. Reason enough to continue with this 2025 edition.

We cycled for the glaciers, but in fact we cycled mainly for ourselves – for the world in which we want to live.